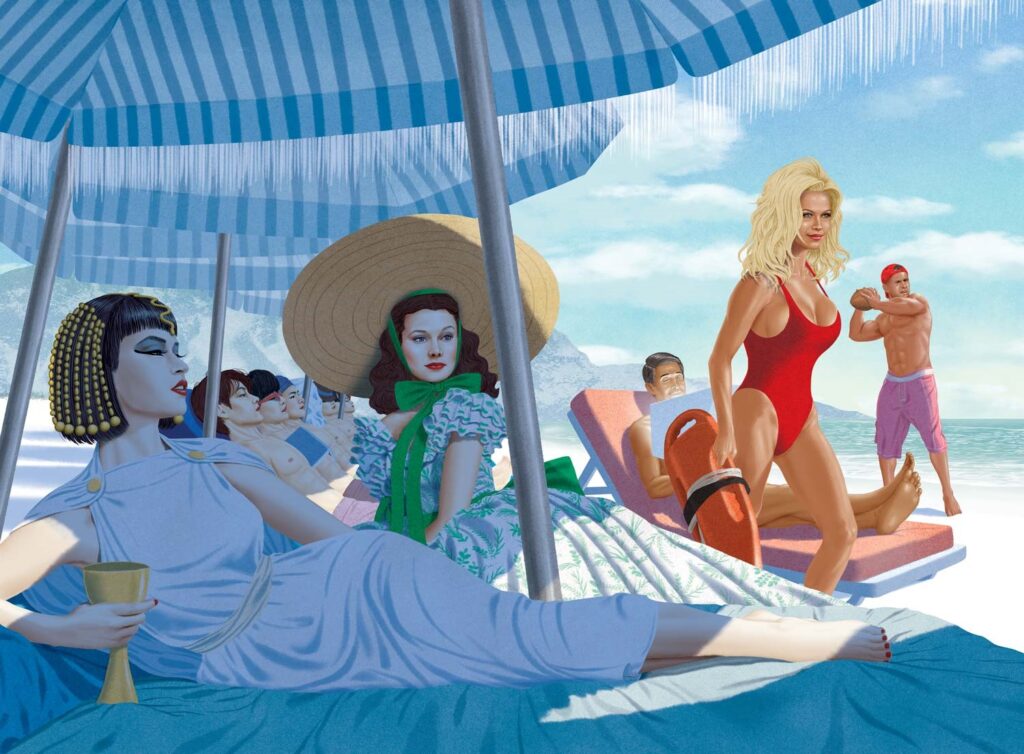

Those who love their tanned skin see a healthy glow. Dermatologists see DNA damage. Historians see cultural influences, from Cleopatra, BTS and Scarlett O’Hara to George Hamilton, Pamela Anderson and The Situation.

The answer is complicated — some people love tanning, and others avoid it like the plague. We explore the deeper meaning behind the desire to alter your skin tone — and what we still can learn.

Illustration by Jason Raish

Being comfortable in our own skin is the ultimate goal, but one visit to the local beach or a scroll through social media suggests we’ve got more work to do. People are still basking in the sun in the pursuit of bronzed skin, and #tanlines has more than 430 million views on TikTok.

Yes, despite the well-established risk between ultraviolet (UV) light and skin cancers, tanning is still part of the culture in the U.S. According to a recent beauty market research report from IBISWorld, tanning salons are a $2.8 billion industry, and, unfortunately, its growth is holding steady. The self-tanner market is also a billion-dollar industry. It may be a safer way to glow, but the message is still clear: People want to be tan. Why?

Multiple studies have shown that people not only feel more attractive when they’re tan but also perceive others as more appealing with a golden glow. How did it become a beauty ideal in the first place? And was it always this way? New York dermatologist and Mohs surgeon Deborah S. Sarnoff, MD, president of The Skin Cancer Foundation, has explored these questions and others throughout her decades of practice and during her worldwide travels.

Bronze Ambition

“In the U.S. and other Western countries, people still think a tan is the epitome of health and beauty,” says Dr. Sarnoff. In the Western world (for the past century or so), acquiring a tan has often appealed to those with the palest skin, who may have been teased for looking “pasty” and wanted to appear healthier and wealthier. (Ironically, this is the skin type most at risk for developing skin cancer.) “But in other parts of the world,” she says, “it’s the complete opposite. Throughout history, pale skin was a status symbol representing wealth, good health, beauty and privilege.”

Dating back to ancient Egypt, Cleopatra reportedly took milk baths to lighten her skin tone via the lactic acid in the dairy drink. During the French Revolution era in the late 1700s, Queen of France Marie Antoinette was known for her alabaster skin and matching powdered hair. (She reportedly made a DIY skin-brightening mask that included milk powder and lemon juice.) Even into the 19th century in the U.S., pale skin was an outward sign that you didn’t spend your days working the land like those in the lower class did. “You were a person of leisure,” says Dr. Sarnoff.

In many Asian countries, women long believed (and many still believe) that pale skin is the ultimate standard of beauty. “Women go to great lengths to protect their skin from the sun,” says Dr. Sarnoff, which helps to prevent skin cancer. However, many also use skin-lightening treatments, from lasers to intravenous infusions, and even topical products that have been known to include potentially harmful ingredients such as arsenic, lead and mercury.

The pursuit of pale started to change in the U.S., though. During the American Industrial Revolution of the late 19th century, the working class relocated to factories, so a tan was no longer a sign of manual labor outdoors. Another game-changer: In the early 1900s, light therapy was harnessed for medicinal benefits, especially for skin conditions, and people began to seek the sun’s rays for their health. In 1903, the first hospital to use sunlight to treat TB opened in Switzerland. Sun therapy (heliotherapy) became the go-to for treating other diseases, too (without yet fully understanding the dangers of sun exposure, of course).

But perhaps the most pivotal moment for the tan occurred in 1923 when fashion icon Coco Chanel accidentally set a new trend. Rumor has it she fell asleep in the sun while on a yacht in the French Riviera and got a sunburn. She healed and returned from the trip with bronzed skin, officially kicking off the tanning craze in the Western world.

“The pendulum swung; it all shifted, almost overnight,” says Dr. Sarnoff. “Suddenly, having a tan meant you had the means to travel and vacation on yachts; it became glamorous, and it stayed that way.” Historians have also linked Chanel’s bold move to women’s liberation. Hemlines were getting shorter, and women were no longer afraid to show a (tan) leg.

Advertisements followed suit, too. In 1927, a swimsuit advertisement showed women covered up on beaches, wearing hats and holding parasols. By 1929, ads from the same company showed women splashing in swimsuits without any of the protective accessories. That same year, Harper’s Bazaar ran a story titled “Shall We Gild the Lily? There is a Technique to a Good Tan — Whether by Fair Means or Fake!” Tan skin was in.

The Tanning Boom

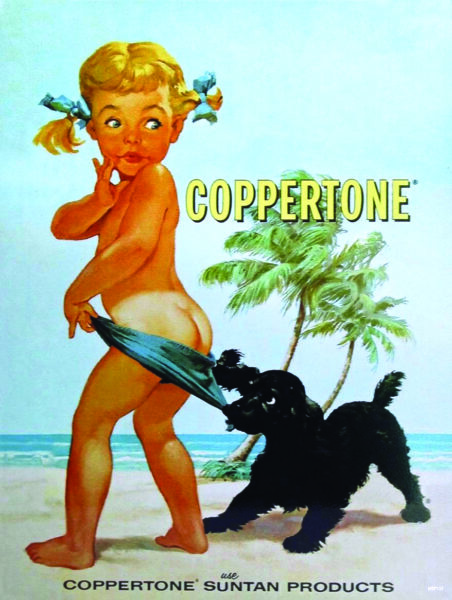

In the 1930s and beyond, the goal was to acquire a tan, even if you couldn’t afford to spend winters on the Côte d’Azur. The aptly named “Golden Age” in Hollywood featured screen stars with radiant, golden skin. “During that time, all the actresses and actors had a deep, dark tan on and off screen,” says Dr. Sarnoff. The consumer suntan industry was born. The first sunscreen was invented in 1938 by Austrian chemist Franz Greiter, who was looking for a way to protect his skin while climbing mountains along the Austrian-Swiss border. But it wasn’t until the 1940s that Coppertone Suntan Cream hit the U.S., an early attempt at sunscreen that combined coconut oil, cocoa butter and a type of petroleum (UV filters came along years later). It was billed as a way to get a better tan without the burn. We later learned, though, that ultraviolet A (UVA), the rays mainly responsible for tanning, also contribute to skin cancer.

The first bikini hit the fashion scene in the 1940s.Women were showing more skin and using various types of creams, oils and foil sun reflectors to get a deeper tan. If you couldn’t achieve a golden glow from the sun, there was self-tanner, with the first one hitting the market in 1960. Dihydroxyacetone (DHA), the ingredient that temporarily darkens skin tone, was later FDA approved in 1977. DHA is still the active ingredient in self-tanners today, but it’s been improved over the years to yield a more natural-looking tan, not the orange “Oompa Loompa” look of the past.

The Dark Side

Of course, all that sun exposure came with a serious consequence: skin cancer. Research in the Journal of Clinical Oncology has shown that between 1950 and 1954, the diagnosis of melanoma was rare, but incidence rates rose 17-fold in men and more than nine-fold in women between 1950 and 2007, with a big surge in the 1970s. World-renowned dermatologist and surgeon Perry Robins, MD, founded The Skin Cancer Foundation in 1979 after witnessing the sudden increase in skin cancers, and the need for awareness, prevention and treatment options.

In 2023, approximately 186,000 new cases of melanoma are estimated to be diagnosed in the U.S., according to the American Cancer Society (more than 97,000 of them invasive). And over the past decade, the number of cases increased by 27 percent. There are also about 3.6 million cases of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and 1.8 million cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) diagnosed in the U.S. every year. Research has shown that about 90 percent of them are associated with UV exposure from the sun.

Knowing these severe risks, why is tanning still popular? “It’s often not until someone gets a skin cancer themselves, or knows someone who did, that they wake up and start using sun protection regularly,” says Dr. Sarnoff. And while the visible signs of sun damage, including wrinkles, brown spots, redness, etc., can be a deterrent, many continue to seek the sun’s rays. “When people see brown spots, they think getting tan will make their skin tone look more even and less blotchy,” she says. “Of course, it only creates further damage — and the potential for skin cancer.”

A Bright Light

While tanning culture is still very much a thing in the U.S., there are hopeful signs of change. In 2015, the FDA proposed a rule that would prohibit minors from using tanning beds and booths. Eight years later, experts are optimistic the rule will be finalized this year. Currently, 44 states and the District of Columbia either ban or regulate the use of indoor tanning beds by minors. And tanning bed use, even among adults, has been declining over the years. Other countries, including Brazil and Australia, have instituted a total ban on indoor tanning. This is where Dr. Sarnoff hopes the U.S. is heading. “It’s not enough to impose age restrictions; indoor tanning is dangerous at all ages,” she says.

Skin-care products with sunscreen are becoming the norm. According to the market research firm Spate, the number of online searches for sunscreen from spring 2019 to spring 2021 increased by 210,000, making it the skin-care product with the highest search growth. The younger, social media-obsessed generation is especially interested in multitasking skin care that includes broad-spectrum sunscreen. “These products make it easier to comply,” says Dr. Sarnoff. “It’s one and done; and I think that’s become trendy now.”

Also, in recognizing the outdated stereotypes and targeted marketing surrounding the tanning industry, there’s been a greater emphasis on celebrating your natural skin tone. We’re even seeing more celebrities bucking the tan trend and embracing their natural skin tone: light, medium or dark. And as more research emerges, we’re learning that although risk can vary, all skin tones need UV protection, not just the fairest of all.

So where does this all leave us? Hopeful. Maybe it will take another it girl to be photographed on a yacht wearing head-to-toe sun protection, but if history has taught us anything, it’s that the pendulum will swing again, and tan skin will be, well, history.

Sign the Petition: Tell the FDA to Ban Teen Tanning

To Sun or Not to Sun: A Timeline of Tan Skin

photo credit: Alamy/Getty Images

- 206 BC – 220 AD – The pale skin trend started in ancient China.

- 51 B – Paleness symbolized wealth, good health and beauty in ancient Egypt.

- 1774 – Marie Antoinette became Queen of France and was known for her powdered skin and hair.

- 1923 – Coco Chanel was famously bronzed after a trip to the French Rivera.

- 1929 – A swimwear brand begins to run ads with women not wearing any sun-protective accessories.

- 1940 – Coppertone launches its Suntan Cream.

- 1962 – Actress Ursula Andress is the first Bond girl and a bronzed bombshell in Dr. No.

- 1979 – The first UV tanning salons open in the U.S.

- 1992 – Actor George Hamilton reaches peak tanning addiction (he knows it’s risky).

- 2007 – A landmark study in the International Journal of Cancer confirms the association of indoor tanning with risk of melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

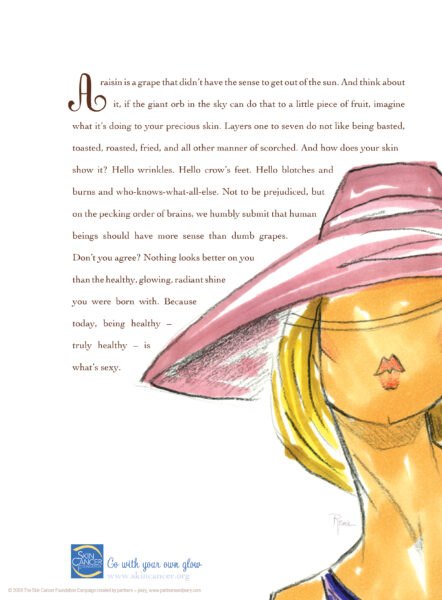

- 2008 – The Skin Cancer Foundation launches its “Go with Your Own Glow” campaign, encouraging women to embrace their natural skin tone.

- 2010 – In season 2 of Jersey Shore, cast member Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino coins the acronym GTL for “gym, tan, laundry.” Dr. Sarnoff sits down with the cast on the prime time show Extra to discuss the dangers of tanning.

- 2011 – The Foundation adds a stringent standard for UVA protection to the Seal of Recommendation requirements, after it was discovered that UVA rays penetrate the skin deeply, contributing to the development of skin cancers.

- 2013 – Actor Hugh Jackman is diagnosed with his first basal cell carcinoma, bringing skin cancer awareness, sun protection and the dangers of tanning into the mainstream. He reportedly has had five more since then.

- 2023 – Social media skinfluencers, such as Julian Sass, PhD (@scamander14 on Instagram), are changing the conversation from tanning to sun protection for all skin tones. Sass tests sunscreens, used as directed, to find those that blend well on skin of color.