After a lifesaving transplant procedure, new risks emerge, including a higher chance of developing skin cancer. Here’s why, and what patients need to know to protect themselves.

By HILARY A. ROBBINS, MSPH, ERIC A. ENGELS, MD, MPH, JOHN P. ROBERTS, MD, and SARAH T. ARRON, MD, PHD

Organ transplants aren’t as rare as you might think. In fact, surgeons perform nearly 30,000 of these lifesaving procedures each year in the United States. The majority are kidney transplants, followed by liver, heart and lung transplants. For people struggling with a failing organ, the prospect of a transplant offers real hope. However, patients often have to wait years because the need for healthy organs far exceeds the number available.

While organ transplantation gives patients who would otherwise have a very short life expectancy the chance to live for many years, it comes with substantial risks. For example, patients must take medication for the rest of their lives to suppress their immune systems so they will not attack and reject the donor organ. Unfortunately, there are many side effects of this treatment, including an increased risk of infections — and a very high risk of certain types of cancer, including skin cancer.

Skin Cancers More Likely After Transplants

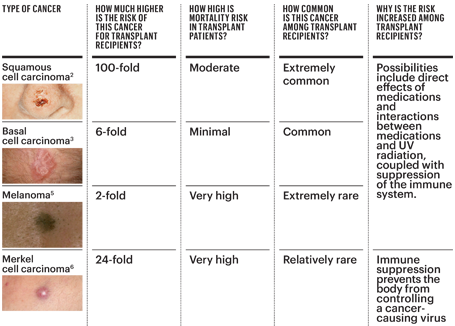

The most common skin cancers after transplant surgery are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), in that order. The risk of SCCs, which develop in skin cells called keratinocytes, is about 100 times higher after a transplant compared with the general population’s risk. These lesions usually begin to appear three to five years after transplantation. While basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in the general population, it occurs less frequently than SCC in transplant patients. Even so, the risk of developing a BCC after transplantation is six times higher than in the general population.

Risks of Four Types of Skin Cancer After Transplantation

Until recently, the impact of transplants on melanoma, a potentially deadly skin cancer of the pigment-producing cells (melanocytes), and Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare skin cancer, had not been very closely studied. In 2015, however, our investigative teams at the National Cancer Institute, the University of California, San Francisco, and Johns Hopkins University found that melanoma is twice as likely to occur and MCC is 24 times as likely to occur in transplant recipients as in the general population.

These skin cancers also behave differently in transplant patients. Melanoma, MCC and SCC are more likely to metastasize (spread) throughout the body in transplant patients compared with the general population, and we found that melanoma is more likely to be fatal. These lesions and the treatment required to remove them can also cause considerable local damage and can be disfiguring in transplant patients.

Why the Increase in Risk

We don’t know all the reasons for the higher incidence and risk of death from skin cancer in transplant patients. One of the clearest causes, though, is that the anti-rejection drugs patients must take reduce the ability of the immune system to detect and defend against cancer. This necessary immunosuppression can also pave the way for infection by cancer-promoting viruses such as the Merkel cell polyomavirus, associated with MCC.

Many transplant patients are already at a higher risk of skin cancer simply due to being older, male and light-skinned, all factors known to be associated with higher risk. That risk may be further increased by other factors, such as an individual’s previous sun damage and a tendency to burn rather than tan. The vast majority of skin cancers are caused by ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sun exposure, and certain post-transplant medications make the skin more vulnerable to sun damage. These include azathioprine, an immune suppressant, and voriconazole, which is used to prevent or treat fungal infections. Another side effect of UV exposure is reduced immune function, which makes it all the more dangerous for transplant patients, who already experience drug-induced immunosuppression.

Sun Safety Reduces the Risks

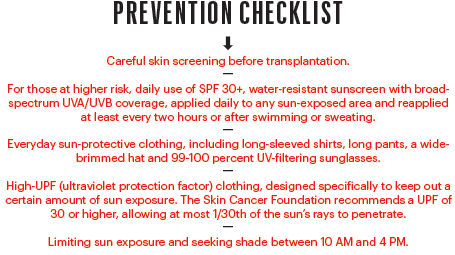

Fortunately, transplant recipients can take many steps to prevent skin cancer and/or detect it at an early stage when it is more likely to be cured with surgery alone. Even though many older recipients had sun damage before their transplant, careful and consistent sun protection can reduce additional damage. While transplant patients don’t have to avoid the sun completely, it is important for them to establish good sun safety habits. Parents and caregivers of children who have received a transplanted organ should also be extremely diligent in protecting their child’s skin from sun damage, since these patients face a lifetime of immunosuppression.

Preventive Treatment

Transplant recipients can also consider several treatments to help reverse sun damage. These can eliminate some precancers and superficial skin cancers that might otherwise develop into invasive disease. Treatments include excision, a light-based therapy called photodynamic therapy and topical medicines such as the chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil or the immune-boosting therapy imiquimod, which can treat a broad area of skin that has many visible or invisible lesions. The oral retinoid acitretin can prevent SCC in transplant recipients, and new data suggest that nicotinamide (a variant of vitamin B3) may also be protective in patients who have already had SCC.

For transplant recipients with a history of skin cancer, doctors may also consider reducing the dosage of the immunosuppressive medications or changing the drugs altogether. For example, newer medications may be less likely to increase photosensitivity.

Follow-up and Early Detection

Since skin cancer in transplant patients can’t always be prevented, patients should undergo regular screening. Most experts recommend annual total-body skin exams for transplant recipients with no history of skin cancer. For those who have had skin cancer or have extensive sun damage, doctors recommend skin checks every six months, or more frequently for patients with a history of multiple skin cancers. Dermatologists should coordinate closely with the patient’s transplant team to optimize care. It is especially important for the patient or dermatologist to tell the transplant team if the patient has been diagnosed with skin cancer, so that the transplant doctors can consider adjusting medications.

The risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma is about 100 times higher after a transplant.

We can’t stress enough the importance of detecting and treating skin cancers in transplant recipients as early as possible, before the cancer can metastasize to distant sites in the body. In our research, we have found that transplant patients have a particularly strong risk of developing melanomas that have already reached an advanced stage when they are detected, especially within the first four years after transplant. One possible explanation is the presence of small, undetected melanomas or precancers prior to transplant that grow rapidly and spread once immunosuppression begins. Therefore, people awaiting a transplant, particularly if they have a history of sun damage, may benefit from a pre-transplant full-body skin exam to find and treat any undetected small melanomas or precancers. Removing these before transplant surgery could prevent aggressive melanomas or SCCs from occurring after the transplant.

When doctors find melanomas in transplant patients, they should schedule regular follow-ups from then on. There is a very high risk of a recurrence or of new lesions appearing throughout the patient’s life, and if not detected early, they may become dangerous.

First Line of Defense: The Patient

In addition to practicing daily sun protection, patients should examine their own skin regularly, enlisting a family member or loved one to check hard-to-see areas such as the back, soles of the feet or between the legs. Look carefully for the ABCDE warning signs of melanoma, and see a dermatologist immediately if you spot anything new, changing or unusual on your skin. By taking the time to protect yourself from skin cancer, and making sure it is treated early if it does occur, you’ll be giving yourself the best assurance of living a long and healthy life with your new organ.

Hilary A. Robbins, MSPH, is a PhD student in the Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Eric A. Engels, MD, MPH, is a senior investigator in the Infections and Immunoepidemiology Branch at the National Cancer Institute and holds an adjunct faculty appointment in the Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

John P. Roberts, MD, is professor and chief, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of California, San Francisco.

Sarah T. Arron, MD, PhD, is an associate professor of dermatology and associate chief of the Dermatologic Surgery and Laser Center at the University of California, San Francisco. She received the Dr. Marcia Robbins-Wilf Research Grant Award from The Skin Cancer Foundation in 2014.

*This article was featured in The Skin Cancer Foundation Journal 2016.